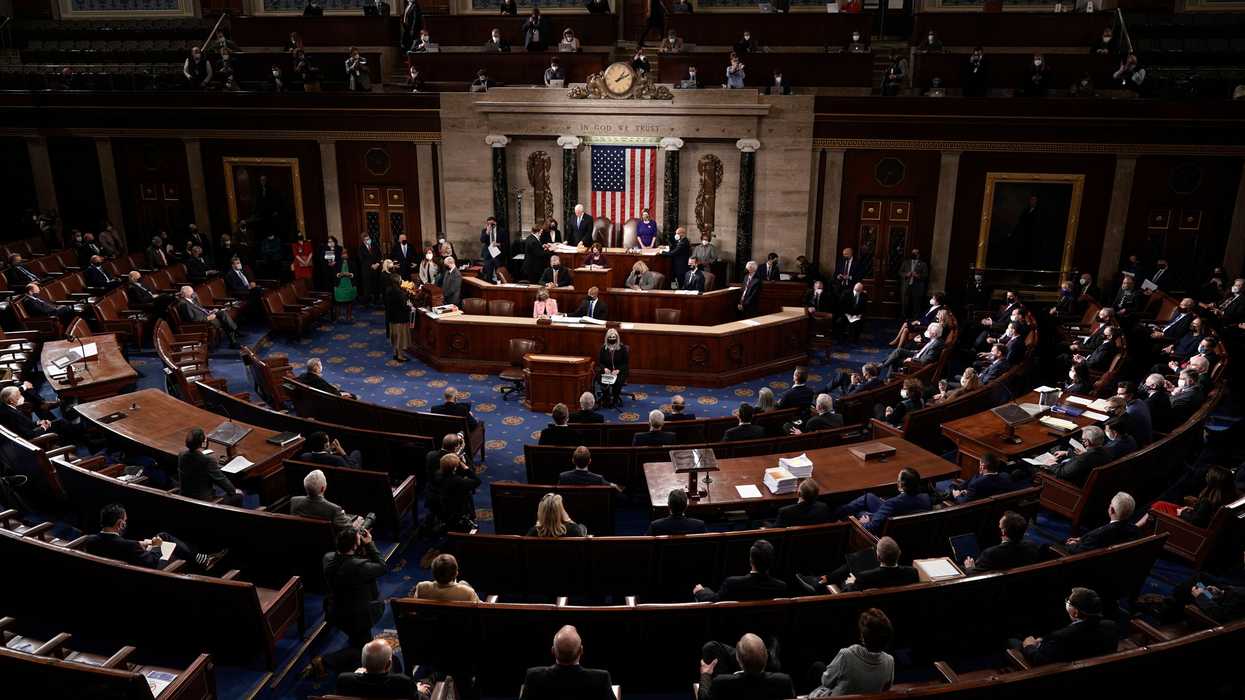

As July 4, 2026, approaches, our country’s upcoming Semiquincentennial is less and less of an anniversary party than a stress test. The United States is a 21st-century superpower attempting to navigate a digitized, polarized world with an operating system that hasn’t been meaningfully updated since the mid-20th century.

From my seat on the Ladue School Board in St. Louis County, Missouri, I see the alternative to our national dysfunction daily. I am privileged to witness that effective governance requires—and incentivizes—compromise.

My fellow board members and I function effectively, not because we are more "neighborly" or morally superior to members of Congress. We function because the machinery of our governance incentivizes our decision to do so. We are bound by mandatory balanced budgets, strict sunshine laws, and inescapable face-to-face accountability. These forces prioritize serving the institution over performing for a camera or chasing social media traction.

Unlike a member of Congress who refuses open town hall meetings with constituents or fundraises off a viral clip of yelling at a witness in an empty committee room, the school board member has nowhere to hide. If the bus doesn’t show up, or the roof leaks, or the math curriculum is failing, I cannot blame "the deep state" or "corporate media." I have to answer to a parent I will inevitably run into at the grocery store that week. Ideology hits a hard ceiling when it meets reality.

The Crisis of Inverted Incentives

Our federal government lacks these enforcement mechanisms. In fact, its incentive structure has been inverted: Conflict is profitable, and resolution is suspect.

In the private sector—or indeed, on a local school board—failure to perform the core function of the job usually results in termination. In Washington, it now means a cable news booking. A government shutdown is not a mark of shame; it is a fundraising opportunity. Because we lack a mechanism that punishes failure, the stakes of our politics have artificially inflated. A Supreme Court vacancy is no longer an administrative event; it is a cultural apocalypse. A presidential election is no longer a transfer of power; it is viewed as a regime change.

At its core, this is not a crisis of the personnel that have been elected; it is a crisis of architecture. We cannot rely on local exceptions to save this republic; we must fix the national foundation. Fortunately, the remedy has been sitting in a drawer for years, albeit largely ignored by Washington.

A Modern “Team of Rivals”

In 2022, the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia convened the Constitution Drafting Project to draft the blueprint we need. They assembled three teams of legal scholars: Conservatives (led by Ilan Wurman), Progressives (led by Caroline Fredrickson), and Libertarians (led by Ilya Shapiro).

This was not a group of centrists splitting the difference to find a lukewarm middle. These were principled partisans recognizing that the current system is serving no one well. Despite conflicting fundamental beliefs, they negotiated a manual for structural repair. They agreed on five constitutional amendments designed to restore the accountability that local boards practice daily.

First, end the Supreme Court’s actuarial lottery. Currently, the balance of power shifts with the health of a single octogenarian. The proposed amendment establishes staggered 18-year term limits for justices. Crucially, it makes appointments automatic if the Senate does not vote within three months—ensuring that a nomination never again languishes in political purgatory.

Second, modernize the executive impeachment process. They proposed a trade-off: Raise the threshold to impeach (to three-fifths of the House) but lower the threshold to convict (to three-fifths of the Senate). This forces a broader consensus to bring charges and inhibits a small partisan minority from shielding a corrupt president.

Third, create a legislative veto. This would empower Congress to rein in the administrative state by overriding agency regulations with majority votes—effectively overturning the Supreme Court’s 1983 INS v. Chadha decision. It compels Congress to take accountability for the laws we live under, rather than delegating difficult choices to unelected agencies.

Fourth, remove the "natural-born" barrier. Allow naturalized citizens with 14 years of citizenship to serve as President—aligning the highest office with America’s sacred promise of meritocracy. After all, we are a nation defined by a creed, not by soil.

Fifth, unlock the amendment process itself. Recognizing that a system unable to adapt is destined to crack, they proposed lowering the threshold for new constitutional amendments to three-fifths of Congress and two-thirds of the states. This change keeps the judiciary from becoming a “permanent constitutional convention.”

The prospect of passing five amendments in our current climate may feel like a fantasy. Skeptics will argue that we cannot agree on the time of day, let alone the supreme law of the land. But the consensus achieved by these scholars—and the daily function of school boards in communities like mine—proves the divide is not unbridgeable.

We are destined to prosper—or fail—alongside the fellow Americans with whom we disagree. This package of amendments is the sturdiest off-ramp from our structural paralysis. It offers a truce based not on agreed ideology, but on shared maintenance of the house we all call home.

We need a federal government that fears failure as much as a school board member fears a rightfully disappointed constituent in the frozen food aisle. As we march toward July 4, 2026, we can keep shouting at one another while the roof caves in, or we can use the tools designed to repair it—should we desire another 250 years.

Peter Gariepy is a CPA and an elected member of the Ladue Schools Board of Education in St. Louis County, Missouri.