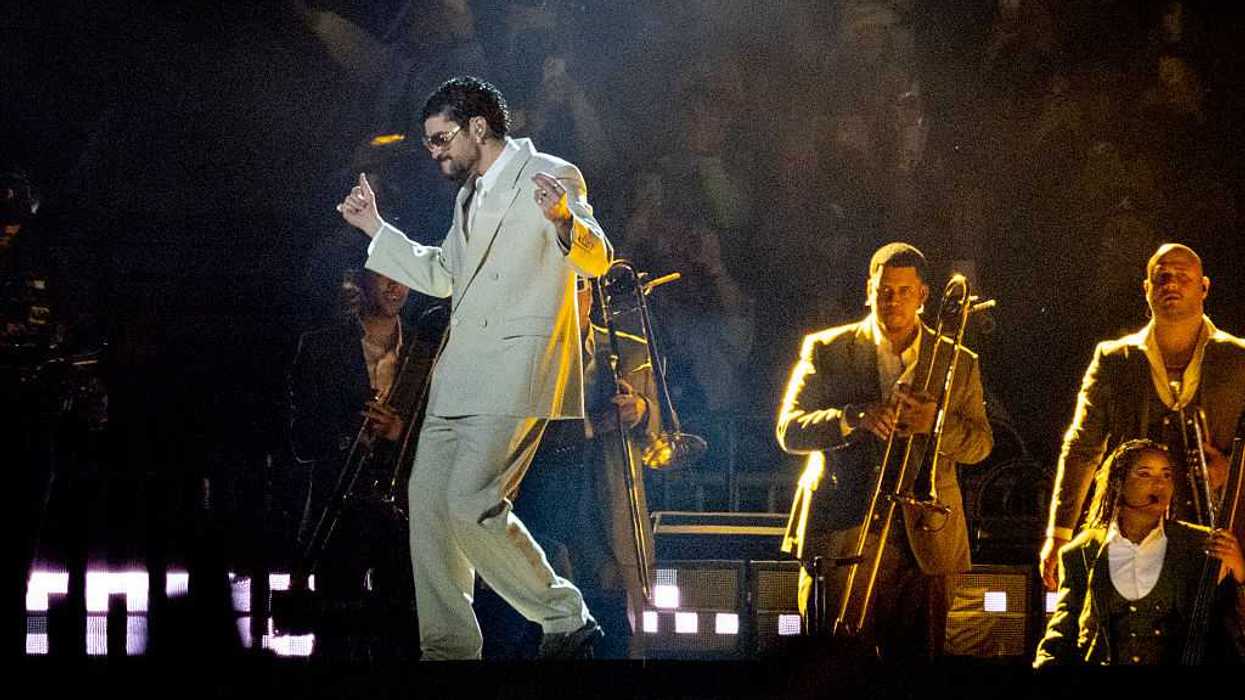

As a child of the 60s and 70s, music shaped my understanding of the world as it does for so many young people stepping into adulthood today. Watching Bad Bunny stand alone at midfield during the Super Bowl, hearing the roar as his first notes hit, and then witnessing the backlash the next day, I felt something familiar to the time of my youth. The styles have changed, but the cultural divide between young and old, between left and right, around music remains the same. The rancor about who gets to speak, who gets to belong, and whose voices are considered “American” remains remarkably constant.

The parallels to the 1980s are striking. President Ronald Reagan, in a 1983 speech lamenting what he saw as the “decay of values” among my generation, warned that “there are those who portray America as a land of racism, violence, and despair. That is not the America we know.” In his radio commentaries, he went further, arguing that “some of the so‑called protest songs seem more intent on tearing down America than lifting it up.” Fast‑forward to today, and the pattern repeats itself. Before the Super Bowl even began, President Trump announced he would boycott the game and blasted the NFL’s choice of performers as “a terrible choice,” setting the tone for the wave of outrage that followed Bad Bunny’s appearance.

And yet, against that backdrop of political condemnation and cultural anxiety, Bad Bunny’s own words told a very different story, a story rooted not in division, but in identity, resilience, and hope. Before he launched into his set, Bad Bunny introduced himself with a message millions of viewers never fully heard:

“My name is Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio. I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. I come from a small place, but with big dreams. And I never, never stopped believing in myself.”

Later, he paused mid‑performance to offer a simple, quiet affirmation. As the hushed crowd held up their cell phones, he spoke:

“To everyone watching: believe in yourselves. You’re worth more than you think. Trust me.”

And he closed with the line that sparked both celebration and outrage:

“The only thing more powerful than hate is love. Love always wins.”

Those words transported me back to the music of my youth — songs that carried their own messages of unity, hope, and resistance, and that were met with their own waves of disdain from older generations.

I remember Jackie DeShannon’s 1965 plea, “What the World Needs Now Is Love,” a song that felt like a lifeline in a turbulent decade. I remember the Beatles’ 1967 anthem “All You Need Is Love,” broadcast to the world during the Vietnam era, insisting that love could still be a unifying force. And I remember being young and idealistic enough to believe John Lennon when he asked us to “imagine” a better world — even as my parents dismissed it all as naïve dreaming.

Yes, we were dreamers. But those dreams connected us. They gave us a sense of shared possibility, even in a fractured nation.

So when I watched the reaction to Bad Bunny, the anger, the cultural panic, the insistence that his presence was somehow un-American, I felt the weight of age and the reality of today's divisions. I wondered whether today's young people are deluding themselves, as my generation was accused of doing. And yet, when I saw him standing alone on the biggest stage in American culture, I also felt the spark of recognition: the belief that music can still call us to something better. I’ve spoken to several young people since Sunday. They were invigorated to see someone from her generation and culture take the spotlight. One said to me, 'It felt like he was speaking directly to us, showing that our voices matter.' Her reflections reminded me of the energy and hope that music brings to every new generation.

We felt that call in 1969 at Woodstock, when hundreds of thousands gathered for peace, love, and music. We felt it again in 1985 when artists across genres united for “We Are the World,” urging us to come together in the face of global suffering. Those lyrics — “when the world must come together as one” — echo loudly in this moment of deep national divide.

Were we naive then? Are we naive now? And if not, what would it take to make this moment different? Take a moment and reflect on a time when you first felt truly connected to a song or an artist's message. What was it about that moment that inspired change within you? Consider how music can challenge our perceptions and ignite action.

I find myself conflicted, as I suspect many Americans are. On an emotional level, I’m moved by Zoom calls, webinars, and civic efforts that urge unity. But emotion alone is not enough. Our country needs more than beautiful ideas. We need a realistic plan to turn these aspirations into something tangible — something that reaches beyond the choir and resonates with the 40 to 50 percent of Americans who feel alienated by calls for unity.

After walking down many roads over the last fifty years, I still hear Bob Dylan’s question:

“How many seas must the white dove sail before she sleeps in the sand?”

I want to believe that "All You Need Is Love." But on days like this, I can't help but wonder whether we're still just "Blowin' in the Wind." Yet despite these doubts, I hold onto the conviction that change is possible. With each new generation, there's fresh hope and an opportunity to build bridges where once there were divides. Let us embrace this moment to foster unity and understanding, because the journey toward a more harmonious future is one worth undertaking. Together, we can transform longing into resolve, guided by the music and messages that continue to inspire us.

David Nevins is the publisher of The Fulcrum and co-founder and board chairman of the Bridge Alliance Education Fund.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift