What if 50 million Americans flooded Congress and the Executive Office with emails and texts, while the leaders of 100 organizations held a joint press conference—issuing releases to every major media outlet with a simple message: “Greenland is not for sale or taking. Uphold your oath of office and protect NATO.”

And when the time was right, the message could focus on Minneapolis. Then Ukraine. Then tariffs. Then Venezuela. Then the Affordable Care Act. And on and on--issues that a majority of Americans support.

Many Americans are angry—and for good reason. They are asking a simple question: What can we do? They watch Congress and the executive branch lurch from crisis to crisis, unable or unwilling to act even when majorities agree. They vote. They protest. They write letters. They donate. And then they watch their elected leaders continue to prioritize party loyalty and gamesmanship over good government.

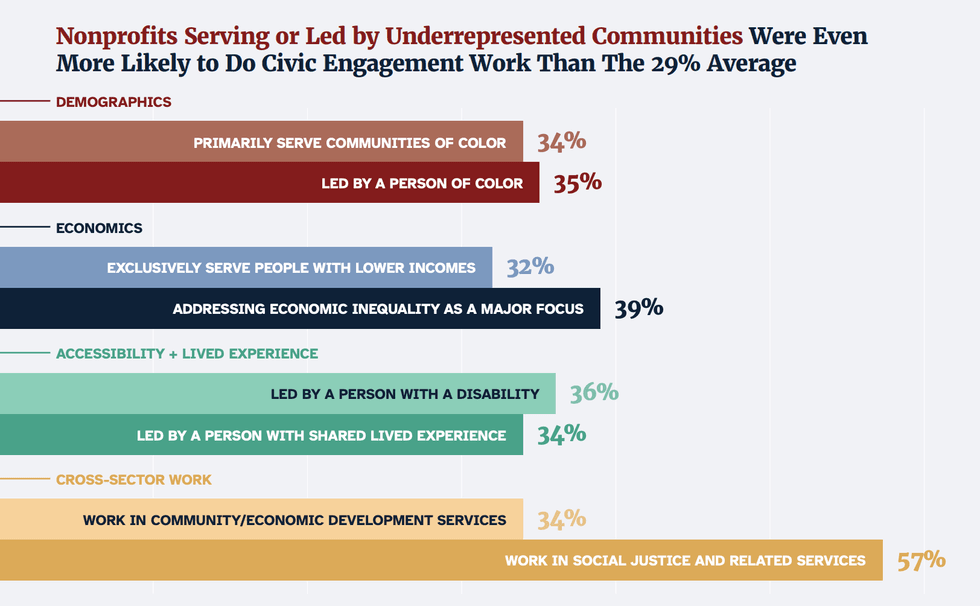

At the same time, hundreds of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), good-government groups, and professional associations operate independently across the country. Many of these nonprofits do extraordinary work in voter rights and education, misinformation management, civic technology, social reform, policy analysis, legal strategy, citizen organizing, and public communication. Each has its own mission, professional staff, and membership base. Most compete for limited funding to advance their priorities.

Yet despite their differences, these organizations share common commitments to the rule of law, constitutional government, and fair decision-making. Taken together, they represent a vast but largely untapped reservoir of civic capacity—a civic infrastructure of millions of members, thousands of trained professionals, and a deep commitment to democratic accountability. The secret weapon of American democracy lies not in inventing something new, but in coordination.

The problem is not civic apathy. It is civic ineffectiveness. Citizens—often members of these organizations—are busy with life’s demands, yet desperate for a way to make their voices matter. The recent “No Kings” protests demonstrated the depth of pent-up civic energy, but such events are limited by geography, time, and personal capacity. Modern American democracy offers remarkably few ways to apply meaningful, timely pressure on elected leaders between elections. Public outrage can dominate headlines, flood social media, and fill city streets—yet still fail to produce a vote, a hearing, or even a serious debate. Expression has replaced leverage.

Government does respond to pressure—just not the kind most citizens are equipped to apply. Lobbyists and well-resourced professional advocates operate continuously, strategically, and with focus. By contrast, public engagement is often episodic and fragmented. Many consequential decisions—committee actions, procedural maneuvers, and individual legislative choices—require pressure at precisely the right moment. The public is rarely organized or mobilized when those moments arrive.

Much of the problem is structural. When the republic was founded, representation was intimate and procedures were far simpler. George Washington endorsed a ratio of one representative for every 30,000 constituents—a scale at which lawmakers could plausibly feel public pressure directly. Today, that ratio is closer to one House member for every 765,000 Americans. In the Senate, the distance is even greater. Over time, congressional rules and procedures have also become increasingly entangled with party power, often disconnected from public will or majority rule. Representation has not merely thinned; it has been stretched to the point of abstraction.

Washington also warned that it was “the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain… the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party.” In today’s context, that warning is urgent. The public’s duty is not abstract. It is concrete: to discourage and restrain governmental excess, demand meaningful oversight, and ensure that government acts on behalf of the people rather than entrenched interests or partisan advantage.

In a nation of 330 million people, fulfilling that duty requires new methods. The original tools of accountability were designed for a democracy far closer to the people it governed. Today’s citizens need mechanisms of pressure that match the scale and complexity of modern governance—methods that are timely, coordinated, and focused on forcing specific actions rather than merely expressing dissatisfaction.

Thus, the need for an American Coalition—not as a political party, not as a protest movement, and not as a replacement for existing organizations, but as a nonpartisan coordination engine capable of translating public frustration into focused governmental action when civic duty calls. Participating organizations would retain their independence and continue pursuing their primary missions. The Coalition’s role would be narrow but powerful: to mobilize collective action at pivotal moments when procedural leverage can force accountability on majority issues.

The country needs a way to aggregate civic concern into sustained, disciplined pressure—pressure capable of compelling hearings, votes, and oversight. The American Coalition would provide that structure by enabling rapid coordination across existing trusted civic networks.

Such an effort would require respected leadership and a highly credible board of directors. Trust is essential. Citizens and organizations must have confidence that the Coalition’s purpose is limited to good governance, not ideological or partisan advantage. Operational staffing would focus on coordination, communications, procedural tracking, transparency, and timely public activation. Clear governance and openness would be essential to sustaining credibility.

Funding could be both democratic and scalable. A “Dollar4Democracy” campaign—limited to one dollar per person per year—would allow millions of Americans to support the Coalition’s operational capacity without ceding influence to large donors or political parties. Beyond funding, the mechanism itself would visibly demonstrate independence, scale, and public legitimacy.

Artificial intelligence would serve as a necessary force multiplier. AI tools can now allow citizen-led organizations with tens of millions of members to operate with a level of coordination once reserved for governments and global corporations. Used responsibly, these systems can personalize communication, identify key decision points, track legislative and procedural developments in real time, and convert broad public concern into targeted civic action.

The mechanics are straightforward. Through coordination, the American Coalition could mobilize members across participating organizations, deliver focused, consistent messaging, generate local and national media attention, track decision-makers' responsiveness, and escalate pressure when necessary. By maintaining a transparent record of actions and outcomes, the Coalition would reinforce accountability and trust. Sustained, concentrated engagement at scale would make inaction increasingly difficult to ignore.

The Coalition would advocate functional governance that respects popular majorities—not partisan agendas. Lawmakers are rarely held accountable for procedural inaction. The American Coalition would change that dynamic by imposing political cost on silence, delay, and avoidance. It would transform fragmented anger into disciplined leverage between elections.

This approach addresses a fundamental weakness in contemporary civic engagement: the challenge of scale and coordination. Citizens are dispersed across a vast landscape of beliefs and priorities. Their concerns, however legitimate, are often drowned out by partisan signaling or competing crises. The American Coalition would channel dispersed energy into a concentrated force, preserving organizational independence while enabling decisive action in pursuit of shared democratic principles.

The stakes are high. Government is becoming increasingly detached from the people it represents. In a country where representation is distant, where procedural maneuvers can thwart majority will, and where party spirit often overwhelms civic purpose, the American Coalition is not merely a new idea—it is a civic imperative.

The civic will is already there. What is missing is a way to harness and focus it between elections. The American Coalition offers Americans a means to fulfill their duty to discourage and restrain governmental excess and to restore accountability to representative democracy. With today’s technology, millions of citizens could finally translate justified frustration into measurable, procedural, and effective action—ensuring that government remains an instrument of the people, not a distant abstraction.

Jeff Dauphin, aka J.P. McJefferson, is retired. Blogging on the "Underpinnings of a Broken Government." Founded and ran two environmental information & newsletter businesses for 36 years. Facilitated enactment of major environmental legislation in Michigan in the 70s. Community planning and engineering. BSCE, Michigan Technological University.

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,