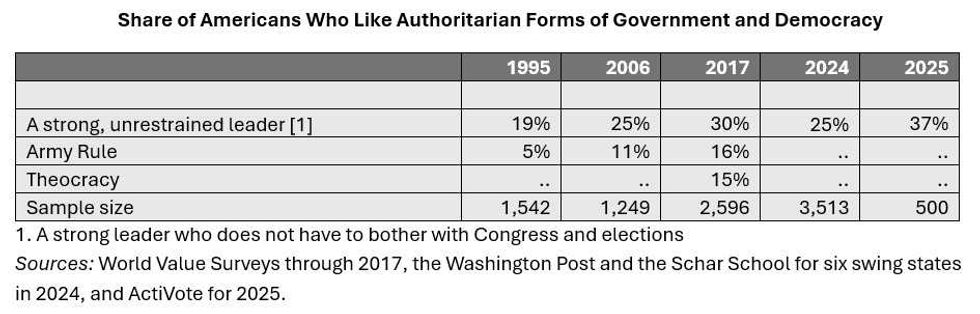

In principle, a person who supports a government of, by, and for the people should not also support a system that concentrates power in the hands of a few. Yet substantial and rising shares of American adults say they view democratic and autocratic forms of governance as equally acceptable. (See Table 1.)

Ambivalence About Autocracy Is Not Confined to One Party

Americans in both major parties show susceptibility to autocracy’s appeal. In this sense, the tension between democratic and autocratic impulses is not new — it persists whenever people seek political advantage by altering the rules of governance.

Consider two examples:

- In 2011, 32% of Democrats said they viewed democracy and a strong, unrestrained leader equally favorably.

- In 2017, the Republican share reached a similarly high level.

(See Figure 1.) These patterns suggest that roughly 18% of Americans are consistently ambivalent, regardless of political context, while the rest shift with partisan winds.

This dynamic aligns with findings from other researchers:

- People tend to be more open to weakening democratic constraints when the president is from their own party, hoping it will help advance their agenda.

- Conversely, they prefer stronger democratic guardrails when the president is from the opposing party, hoping to slow the other side down.

Thus, with President Obama in office in 2011, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to favor a strong, unrestrained leader. The pattern reversed under President Trump in 2017.

Figure 1. Share of Americans Who Were Ambivalent Between Autocracy & Democracy

This self-serving attitude, especially when widely held, allows ambitious politicians to try to weaken democracy to their advantage. It might also indicate a problem in existing civic education programs at all grade levels through college.

Ambivalent Americans Are a Crucial and Reachable Audience

They represent a large pool of potential new support for democracy. In addition, while most are less active politically now, many are open to becoming more so. Imagine how things might change if even half of those people could be inspired to reject the temptations of autocracy and become active supporters of American democracy!

The Center for Free, Fair, and Accountable Democracy, where I serve, is a small 501(c)(3) founded in 2018. We are dedicated to helping more American adults understand why American democracy is valuable enough to defend and improve. Every educational resource we produce is reviewed by at least one conservative and one progressive expert. (Learn more at https://cffad.org/.)

We have begun researching this ambivalent population to develop a theory of change aimed at helping them recognize the connection between the quality of their lives and the quality of American democracy — and how their participation can improve both.

Our work draws on evidence from scholars and practitioners in civic education, political participation, democratic resilience, and political psychology. We are examining what distinguishes ambivalent Americans, how to reach them, and how to support meaningful shifts in their attitudes and behaviors.

Could Two Shifts Make a Meaningful Difference?

Our emerging theory of change suggests that an ambivalent person’s openness to autocracy could be significantly reduced by encouraging them to do just two things:

- Update their understanding of what is essential to democracy.

- Abandon a politically expedient mindset that prioritizes results by any means over accountable representation and freedom.

Importantly, our analysis so far indicates that it may not be necessary to change deeply held values or reduce ideological polarization. The role of affective (emotional) polarization remains uncertain — though the shifting partisan patterns we observed suggest it may matter. We are gathering more evidence.

We recognize the challenge ahead. Capturing and sustaining the attention of adults who are busy, overwhelmed, or disengaged is no small task. But the stakes are high, and the potential impact is real.

If you have insights, questions, or interest in collaborating, we welcome your outreach at team@cffad.orgDoug Addison is the founder of The Center for Free, Fair, and Accountable Democracy. He and his organization are working to build an understanding of why American democracy is valuable enough to defend and improve

.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift