“Affordability” over the cost of living has been in the news a lot lately. It’s popping up in political campaigns, from the governor’s races in New Jersey and Virginia to the mayor’s races in New York City and Seattle. President Donald Trump calls the term a “hoax” and a “con job” by Democrats, and it’s true that the inflation rate hasn’t increased much since Trump began his second term in January.

But a number of reports show Americans are struggling with high costs for essentials like food, housing, and utilities, leaving many families feeling financially pinched. Total consumer spending over the Black Friday-Thanksgiving weekend buying binge actually increased this year, but a Salesforce study found that’s because prices were about 7% higher than last year’s blitz. Consumers actually bought 2% fewer items at checkout.

Moreover, according to an analysis by Mark Zandi from Moody's Analytics, consumer spending has been driven largely by high-income households, with the top 10% accounting for nearly half of all spending. "That group has always accounted for a much larger share of spending, but that share has risen significantly over time, and now is the highest it's ever been," Zandi told CBS News.

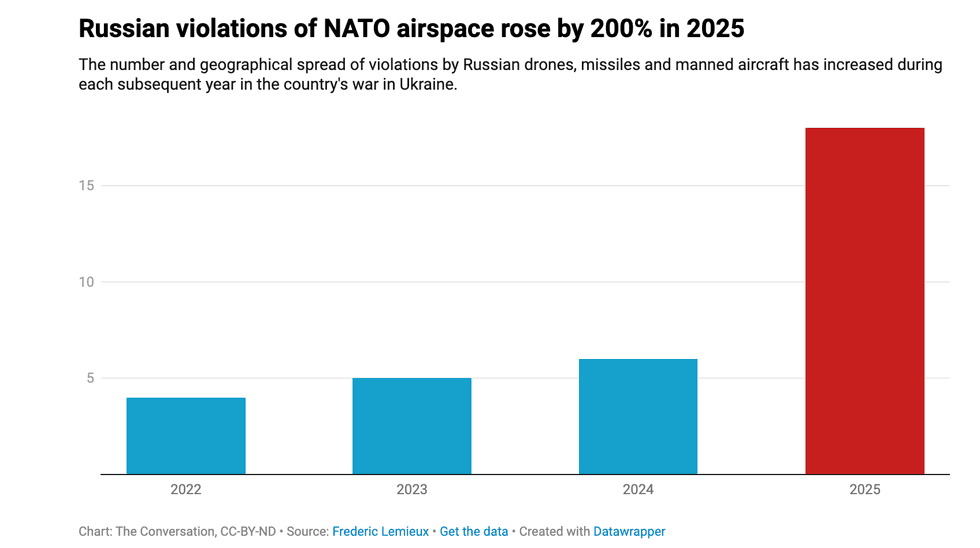

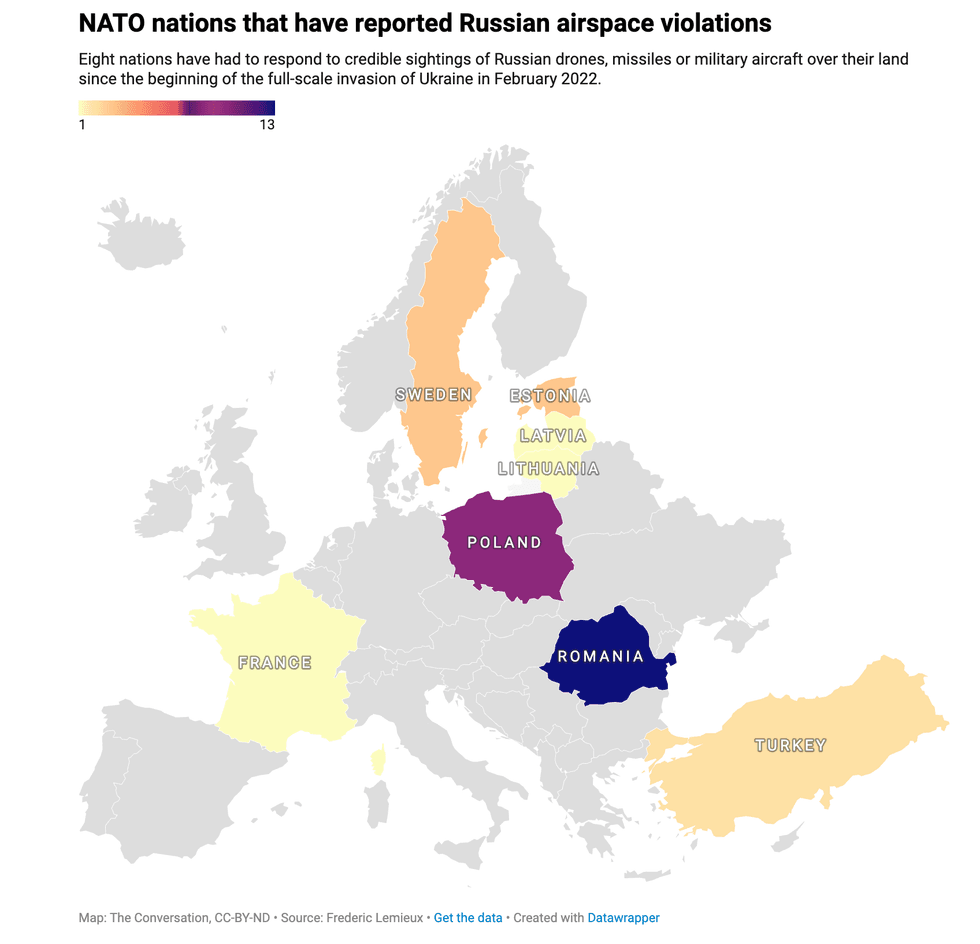

While partisan sides fight over whether there is an affordability gap, other experts predict it could worsen significantly as we enter the AI age. If intelligent machines are increasingly able to do more and more human jobs, workers' bargaining power to capture their fair share of the accumulating wealth will diminish. Wages will likely continue lagging behind economic growth and price increases. It’s like a hamster on the wheel, chasing its own tail, trying to keep up. So what’s the solution?

The Kelso alternative of universal capitalism

Interestingly, several decades ago, an American original named Louis O. Kelso proposed an innovative way to help every American have a bigger share of the economic pie. Kelso was an economic trailblazer and financial genius who, in the 1970s, proposed a new approach to a more broadly shared prosperity that broke with the usual “Tax the rich and redistribute the income” model that became popular in the US, Europe, Canada, and elsewhere.

Instead, to a national audience that heard Kelso through interviews on shows like 60 Minutes with Mike Wallace and profiles in the New York Times and Time, and through his bestselling book The Capitalist Manifesto, Kelso proposed spreading ownership of capital assets to everyday Americans. In an economy where the top 10% of affluent Americans own 93% of all stocks, he proposed that more Americans should own more stock, so that they, too, could benefit from rising profits in successful companies and from the innovation of new technologies, which often drive the rising profits.

Louis Kelso called his vision “universal capitalism.” His philosophy was rooted in the same principles that had motivated America’s founders like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton, and the Populist movement of the late 19th century, who were strong proponents of widespread property ownership -- in the form of land -- as a catalyst for both economic liberty and political freedom. But in Kelso’s plan, farmland was replaced by stock ownership in valuable companies.

Worker-owners for a “piece of the action”

Pie in the sky, you say? Louis Kelso demonstrated the viability of his vision with his invention of what is known as the employee stock ownership plan (ESOP). Today, ESOPs are used by some 6,300 businesses, including Walmart, Lowe’s, Southwest Airlines, Recology, and Publix Super Markets, to financially empower 15 million worker-owners who are compensated with stock in the companies they work for, in addition to their wages. That’s a greater number of workers than those who are labor union members.

Kelso’s ESOP legislation in the 1970s attracted broad support from the right and the left, from leading Democrats and Republicans, including Presidents Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon, and today is still supported by both Democratic and Republican party platforms – even as Kelso’s ideas were scorned by mainstream economists, like Milton Friedman.

While ESOPs benefit the employees of a particular company, Kelso proposed other financing vehicles as part of a broader call for universal capitalism designed to provide ownership of key capital assets to more people. For example, Kelso adapted one of his financing techniques, a Consumer Stock Ownership Plan (CSOP), to help a co-op of nearly 5,000 struggling farmers in California’s Central Valley secure a bank loan to purchase their own fertilizer plant. The bank loan was repaid from the fertilizer plant's future profits. That got the farmers out from under the exploitative boot heel of the oil companies that monopolized the fertilizer industry. The farmers paid off the bank loan in record time, even as they saved a billion dollars by drastically reducing fertilizer prices.

Kelso also had plans for how to use his financing mechanisms to not only house the poor but to turn them into owners of their own homes. One of Kelso’s original plans became what is known today as the Alaska Permanent Fund, which allows every Alaskan to share equally in the state’s oil wealth, an early and successful example of Universal Basic Income. Without Kelso’s influence, there would likely be no IRAs, 401(k)s, and other savings vehicles that eventually were birthed out of the “shareholders for all” movement that he spawned. He had another plan, called a General Stock Ownership Plan (GSOP), that would have created a kind of sovereign wealth fund in which a portfolio of stock investments on behalf of large populations of Americans would provide a second income stream for those people, beyond their wages, out of the future returns on those investments.

The role of technology in wealth creation

Kelso anchored his initiatives in a deep understanding of the economic impacts of new technologies and scientific innovation. Kelso was one of the first to fully grasp the ramifications of the insight that French economist Thomas Piketty made famous 40 years later—that the rate of return on capital investment naturally exceeds the economic growth rate, and therefore the rate of wage increases. Kelso recognized that capitalism has a natural bias toward the concentration of ownership, particularly of the machines and technologies that drive productivity and profits. Consequently, financial wealth accumulates much faster than wage income, and that’s why the small 10 percent elite of wealthy investors get richer while the 90% of wage-earners tread water or worse. As the US stands on the cusp of an AI revolution dominated by a handful of tech companies, Kelso’s warning about the negative impacts when only a small handful of wealthy investors benefit financially from technological advancement has never been more urgent.

Owners By the Millions

In today’s world of unbalanced inequality, of the 1% vs the 99% riven with populist grievances, universal capitalism is more relevant than ever. Kelso’s economic vision advances the common-sense notion that the vast majority of Americans should be owners of the businesses in which they work, as well as of the economy in general. Interestingly, Kelso, who was a corporate attorney by profession, was not some leftie liberal. His own politics could best be described as libertarian-humanitarian. And he was also anti-communist but critical of American capitalism. In fact, he thought that, during the economic doldrums of the 1970s, he was saving capitalism from the allure of communism/socialism.

The Kelso vision is urgently relevant today because it is a story about economic fairness and the future of the American Dream. During a time of federal retrenchment and cash-strapped states and cities, Kelso’s creative financing vehicles are increasingly being discussed as potential ways to fund housing, college tuition, public ownership of utilities, universal basic income, public transportation, and even reparations to slave descendants, without dipping into the public treasury.

With the US seeking a politically viable way to move past toxic populism into a new era of bipartisanship, the time is ripe to reintroduce Louis O. Kelso and his “positive populist” vision to new generations.

Steven Hill was policy director for the Center for Humane Technology, co-founder of FairVote and political reform director at New America. You can reach him on X @StevenHill1776.