Imagine there was a way to discourage states from passing photo voter ID laws, restricting early voting, purging voter registration rolls, or otherwise suppressing voter turnout. What if any state that did so risked losing seats in the House of Representatives?

Surprisingly, this is not merely an idle fantasy of voting rights activists, but an actual plan envisioned in Section 2 of the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868 – but never enforced.

Constitutional rights often exist without clear enforcement mechanisms, but attorney Jared Pettinato thinks he’s found one. He’s filed a lawsuit against the United States Census Bureau, aiming to require it to enforce Section 2. I follow the case in my documentary, FOURTEEN SECTION TWO, now in post-production. Check out the trailer below.

As you can tell, Pettinato wants to make Section 2 an active part of the Constitution. But why did it become inactive in the first place? To answer that question, we need some additional historical context.

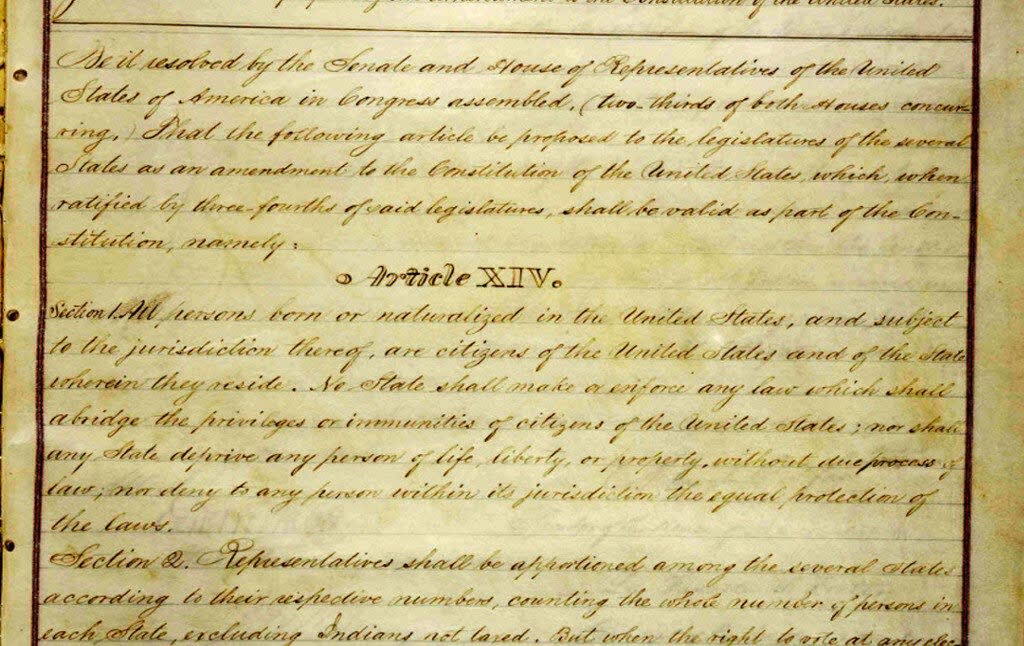

Most of us know about the 14th Amendment because of Section 1, which enshrined birthright citizenship, due process, and equal protection within the Constitution. But for the framers, Section 2 was potentially more important because it aimed to ensure that newly emancipated Black men in the South would be able to vote – and by doing so, keep in power the Republican party that won the Civil War.

Photo of the 14th Amendment.

Section 2 begins by stating, “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State.” It’s not obvious from the text, but this provision abolished the notorious Three-fifths Compromise from the original Constitution. With the adoption of the 14th Amendment, Black people would be counted in full for the purposes of Congressional apportionment.

The framers had a problem, though. Because the South’s full Black population would now be counted, the Confederate states would re-enter the Union with more representation in the House than they had before the Civil War. If former Confederates remained in power in those states, they would suppress the Black vote and then reassert their dominance over the national government.

The Republicans could not abide this possibility, but at the time, they didn’t have the votes for the obvious solution — prohibiting states from denying citizens the right to vote on the basis of race. That would come later in the 15th Amendment.

Instead, they developed a rather convoluted solution in the rest of Section 2. The states would be allowed to abridge or deny the vote as they wished, but there would be a penalty for doing so. If, say, 10% of potential voters could not vote, then the state’s population would be reduced by that same 10% when seats were apportioned in the House. A state could therefore wind up with fewer seats than it would normally be entitled to.

No state would risk such a penalty, which would make Section 2 a strong safeguard of voting rights. But when Congress attempted to enforce Section 2 in the 1870 census, it quickly became clear that it was nearly impossible to gather reliable data about voter denials and abridgements. As enthusiasm for Reconstruction waned, Congress made even less effort to enforce Section 2. It remained in the Constitution as a dead letter. And it mostly stayed that way until 2022, when Jared Pettinato brought his lawsuit.

The lawsuit and the Section 2 background raise many questions. Most obviously, how does a section of the 14th Amendment, a part of “the highest law in the land,” go unenforced for more than 150 years? Is the strange history of Section 2 a quirk or a canary in a coal mine, warning us that something has gone wrong with our Constitutional order?

This is perhaps a more relevant question than I would like it to be. But there’s no denying that much of what we took for granted in the Constitution is up for debate. Everything from freedom of speech to the right to bear arms to birthright citizenship to due process seems less certain than it was not long ago. Perhaps we’ve believed that the Constitution guaranteed us rights because of the words on the page or the orders of a court. But it’s now clearer than ever that the words and the orders relied on a system that may be breaking down.

With so much at stake, why make a film about a part of the Constitution that everyone had pretty much agreed to forget? I think reviving a debate about Section 2 of the 14th Amendment is good for us. It forces us to think about what rights we really want to have and what we need to do to secure them. Clearly, just writing them down is not enough.

When our current crises pass, we cannot simply return to the status quo ante. There are moments in our history that force a rupture in and reimagination of the Constitution. Reconstruction was one. Now may well be another. I hope that studying the history of Section 2 might help us learn from the past, navigate this moment, and find something better on the other side.

A film is a unique way to make that effort. It takes Constitutional questions out of the abstract and makes them real for a wider audience. If you’d like to be a part of the journey, you can subscribe to my newsletter.

A Constitutional Provision We Ignored for 150 Years was first published on the Substack channel, Expand Democracy and was republished with permission.

Todd Drezner is a documentarian, producer, and writer.