The Supreme Court on Dec. 5, 2025, agreed to review the long-simmering controversy over birthright citizenship. It will likely hand down a ruling next summer.

In January 2025, President Donald Trump issued an executive order removing the recognition of citizenship for the U.S.-born children of both immigrants here illegally and visitors here only temporarily. The new rule is not retroactive. This change in long-standing U.S. policy sparked a wave of litigation culminating in Trump v. Washington, an appeal by Trump to remove the injunction put in place by federal courts.

When the justices weigh the arguments, they will focus on the meaning of the first sentence of the 14th Amendment, known as the citizenship clause: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Both sides agree that to be granted birthright citizenship under the Constitution, a child must be born inside U.S. borders and the parents must be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. However, each side will give a very different interpretation of what the second requirement means. Who falls under “the jurisdiction” of the United States in this context?

As a close observer of the court, I anticipate a divided outcome grounded in strong arguments from each side.

Arguments for automatic citizenship

Simply put, the argument against the Trump administration is that the 14th Amendment’s expansion of citizenship after the eradication of slavery was meant to be broad rather than narrow, encompassing not only formerly enslaved Black people but all persons who arrived on U.S. soil under the protection of the Constitution.

The Civil War amendments – the 13th, 14th and 15th – established inherent equality as a constitutional value, which embraced all persons born in the nation without reference to race, ethnicity or origin.

One of the strongest arguments that automatic citizenship is the meaning of the Constitution is long-standing practice. Citizenship by birth regardless of parental status – with few exceptions – has been the effective rule since the time of America’s founding.

Advocates also point to precedent: the landmark case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898. When an American-born descendant of resident noncitizens sued after being refused re-entry to San Francisco under the Chinese Exclusion Act, the court recognized his natural-born citizenship.

If we read the Constitution in a living fashion – emphasizing the evolution of American beliefs and values over time – the constitutional commitment to broad citizenship grounded in equality, regardless of ethnicity or economic status, seems even more clear.

PeopleHowever, advocates must try to convince the court’s originalists – Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett – who read the Constitution based on its meaning when it was adopted.

The originalist argument in favor of birthright citizenship is that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” was meant to invoke only a small set of exceptions found in traditional British common law. In the Wong Kim Ark ruling, the court relied on this “customary law of England, brought to America by the colonists.”

One exception to birthright citizenship covered by this line of rulings is the child of a foreign diplomat, whose parents represent the interests of another country. Another exception is the children of invading foreign armies. A third exception discussed explicitly by the framers of the 14th Amendment was Native Americans, who at the time were understood to be under the jurisdiction of their tribal government as a separate sovereign. That category of exclusion faded away after Congress recognized the citizenship of Native Americans in 1924.

The advocates of automatic birthright citizenship conclude that whether the 14th Amendment is interpreted in a living or in an original way, its small set of exceptions do not override its broad message of citizenship grounded in human equality.

Opposition to birthright citizenship

The opposing argument begins with a simple intuition: In a society defined by self-government, as America is, there is no such thing as citizenship without consent. In the same way that an American citizen cannot declare himself a French citizen and vote in French elections without consent from the French government, a foreign national cannot declare himself a U.S. citizen without consent.

This argument emphasizes that citizenship in a democracy means holding equal political power over our collective decisions. That is something only existing citizens hold the right to offer to others, something which must be decided through elections and the lawmaking process.

The court’s ruling in Elk v. Wilkins in 1884 – just 16 years after the ratification of the 14th Amendment – endorses “the principle that no one can become a citizen of a nation without its consent.” By making entry into the United States without approval a federal offense, Congress has effectively denied that consent.

Scholars who support this view argue that the 14th Amendment does not provide this consent. Instead it sets a limitation. To the authors of the 14th Amendment, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” conveyed a limit to natural citizenship grounded in mutual allegiance. That means if people are free to deny their old national allegiance, and an independent nation is free to decide its own membership, the recognition of a new national identity must be mutual.

Immigrants living in the United States illegally have not accepted the sovereignty of the nation’s laws. On the other side of the coin, the government has not officially accepted them as residents under its protection.

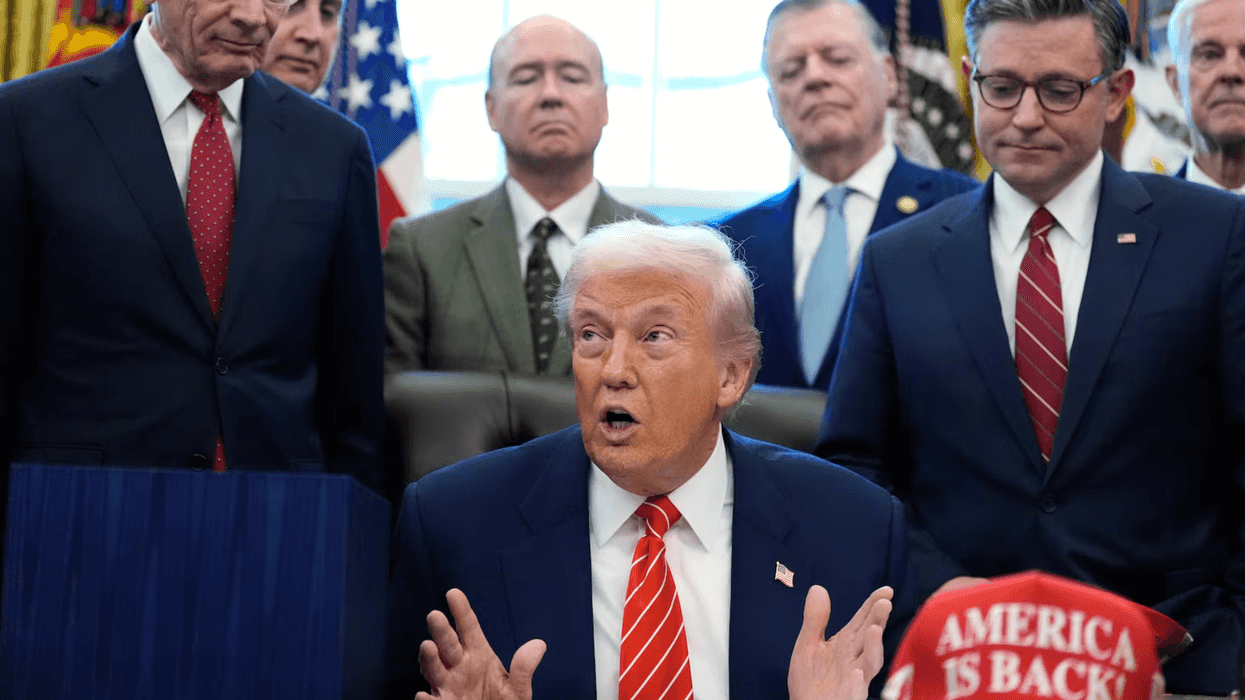

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on birthright citizenship in the Oval Office on Jan. 20, 2025. AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on birthright citizenship in the Oval Office on Jan. 20, 2025. AP Photo/Evan Vucci, FileIf mutual recognition of allegiance is the meaning of the 14th Amendment, the Trump administration has not violated it.

The opponents of birthright citizenship argue that the Wong Kim Ark ruling has been misrepresented. In that case, the court only considered permanent legal residents like Wong Kim Ark’s parents, but not residents here illegally or temporarily. The focus on British common law in that ruling is simply misguided because the findings of Calvin’s Case or any other precedents dealing with British subjects were voided by the American Revolution.

In this view, the Declaration of Independence replaced subjects with citizens. The power to determine national membership was taken away from kings and placed in the hands of democratic majorities.

For opponents of birthright citizenship, the 14th Amendment does not take that power away from citizens but instead codifies the rule that mutual consent is the touchstone of admission. The requirement to be “subject to the jurisdiction” provides the mechanism of that consent.

Congress can determine who is accepted as a member of the national community under its jurisdiction. In this view, Congress – and the American people – have spoken: Current federal laws make entry into U.S. borders without permission a crime rather than a forced acceptance of political membership.

What might happen

The court will likely announce a ruling in summer 2026 before early July, just in time for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The court will ultimately decide whether the Constitution endorses the declaration’s invocation of essential equality or its creation of a sovereign people empowered to determine the boundaries of national membership.

The court’s three Democratic-appointed justices – Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor – will surely side against the Trump administration. The six Republican-appointed justices seem likely to divide, a symptom of disagreements within the originalist camp.

The liberal justices need at least two of the conservatives to join them to form a majority of five to uphold universal birthright citizenship. This will likely be some combination of Chief Justice John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

The Trump administration will prevail only if five out of the six conservatives reject the British common law foundations of the Wong Kim Ark ruling in favor of citizenship by consent alone.

America should know by July Fourth.

Morgan Marietta is a Professor of American Civics at the University of Tennessee.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room