Frazier is an assistant professor at the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University. Starting this summer, he will serve as a Tarbell fellow.

“That’s the wrong question.”

In the most recent season of “True Detective,” Jodie Foster plays a detective in Alaska. Her character has a knack for pushing other officers to ask better questions about the complex case in their hands. Unsurprisingly, it annoys the heck out of her colleagues. Also unsurprisingly, it helps them get to the heart of the case a lot faster than if they had chased the wrong lead.

For a long time American voters have been asking the wrong questions. When candidates attend town halls or host “Ask Me Anything” sessions on social media, voters tend to ask questions like “What are you going to do about issue X?” and “What’s your stance on conflict Y?” In general we ask questions that place the burden, duties and power on candidates rather than on us, the people, the “sovereigns” of this entire system of governance.

The passive posture inherent to this sort of questioning has two negative outcomes. First, it diminishes our own sense of responsibility for the success of our democracy. When you think someone else holds the keys to your future, it’s easy to deflect blame for when things go wrong. A lot of folks these days seem to place blame for the current state of our democracy on a single party, a single branch or a single official. This mindset is in part because we’ve become so used to asking the wrong questions.

Second, our focus on other actors in our democracy decreases the odds of collectively demanding reform. It works like this: As long as we dominate to point fingers at others, we will be distracted from finding ways to collaborate.

To reclaim the people’s power over our democracy we need to start asking better questions. Here’s a short list that I’d recommend — I’m eager to hear from you all.

What’s stopping me from being more involved politically? What resources, opportunities and issues would propel me to be a more active participant?

Do I feel as though my local, state and federal leaders understand my concerns and lived reality? If not, what do I think is essential for them to understand?

How do my friends impact my political views and level of engagement? Which pals could I talk more with about these issues? Who might have suggestions for good news outlets and engagement opportunities?

It’s no secret that a lot of action can simply come from recognizing that you’re in a position of influence. Don’t get me wrong — there are a heck of a lot of barriers to improving the state of our democratic discourse and the quality of our government. The people have less money and more problems than special interests. But we have something they never will — formal recognition as sovereigns over our system.

By asking questions about how we can more responsibly and effectively use that role to create lasting change, we can sow the seeds for a democracy that matches our expectations and allows us to reach our potential.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t ask plenty of questions of our elected officials — it’s just to emphasize that we’ve been neglecting some other important inquiries for far too long. So the next time a friend or family member questions why “they” or “that party” isn’t doing X or Y, perhaps remind them that they’re asking the wrong question.

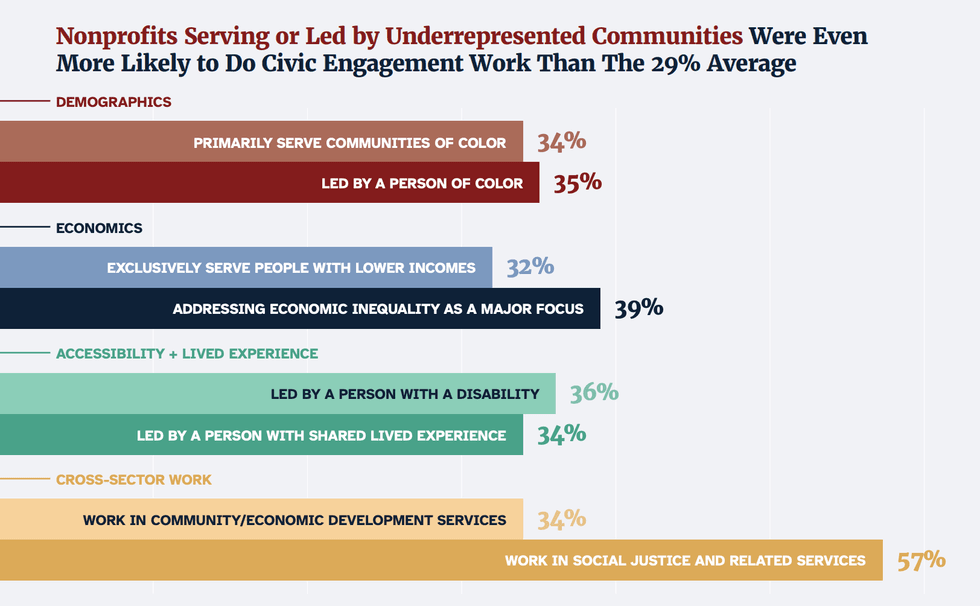

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift