Like many people over 60 and thinking seriously about retirement, I’ve been paying closer attention to Social Security, and recent changes have made me concerned.

Since its creation during the Great Depression, Social Security has been one of the most successful federal programs in U.S. history. It has survived wars, recessions, demographic change, and repeated ideological attacks, yet it continues to do what it was designed to do: provide a basic floor of income security for older Americans. Before Social Security, old age often meant poverty, dependence on family, or institutionalization. After its adoption, a decent retirement became achievable for millions.

The data tells a clear story about poverty reduction. In 1959, more than one in three seniors lived below the poverty line. Today, that figure is closer to one in ten, largely because of Social Security. Remove the program from the equation, and senior poverty would surge to levels not seen in generations. This is not a marginal safety net. It is the central pillar of retirement security for a large share of older Americans, including roughly 40 percent of retirees who rely on it for at least half of their income.

International comparisons reinforce the point. Many peer democracies, including Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands, rely more heavily on public pensions than the United States, but the underlying logic is the same: predictable, universal retirement income reduces elder poverty. Higher senior poverty rates in the U.S. reflect the thinness of the broader retirement system, not a failure of Social Security itself. In practice, the program often compensates for gaps elsewhere in the American welfare state.

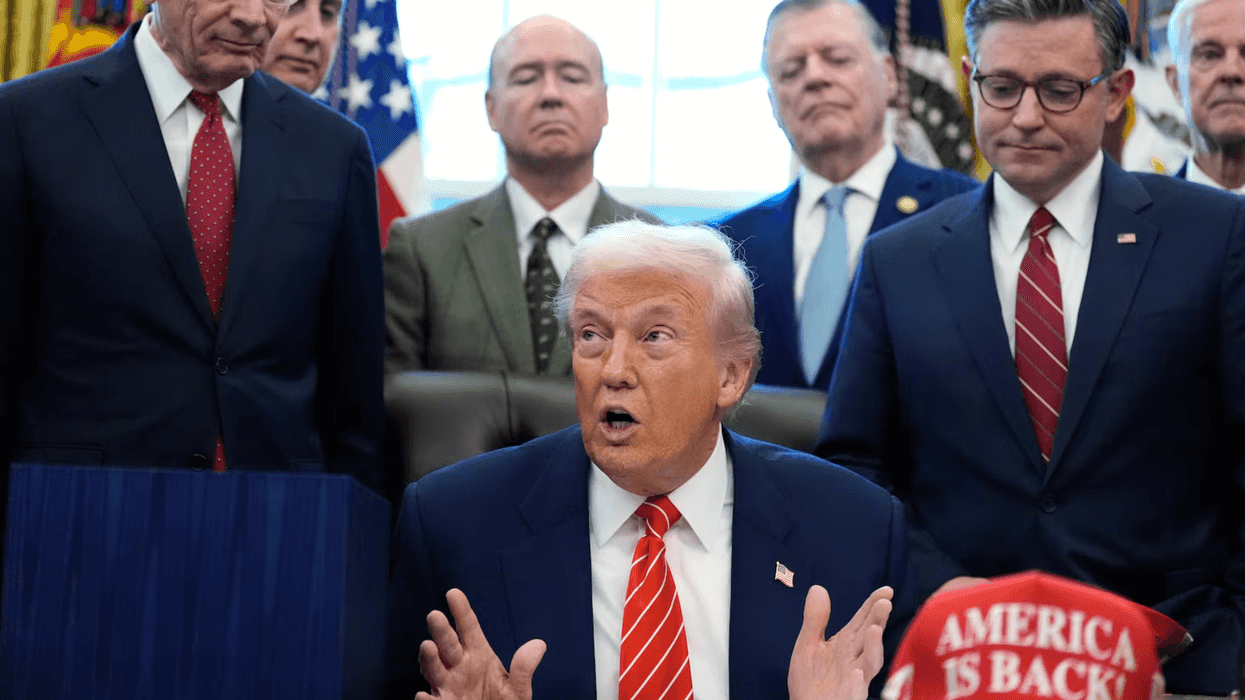

That record makes Social Security’s trajectory under President Trump more concerning. Recent changes do not amount to sweeping benefit cuts, but they do alter how the program is funded, administered, and accessed. Social Security is not a failed program in need of radical reinvention. It is a successful one under strain, increasingly asked to absorb rising health care costs, disappearing pensions, and widening inequality. The question is not whether Social Security works. It plainly does. The question is whether policymakers will strengthen it or quietly undermine it through incremental changes that shift risk back onto seniors.

The First Wave of Changes

The changes that come next emerge less from headline legislation than from a steady accumulation of administrative decisions that reshape how the program functions day to day. They also fit squarely within the administration’s broader Department of Government Efficiency agenda, which emphasizes cost containment, automation, and workforce reduction across federal agencies.

This year, the Trump administration began altering Social Security through administrative and operational moves rather than major legislation. Cast as efficiency and modernization measures, these changes nonetheless carry real consequences for beneficiaries.

First, the administration ended Biden-era limits on overpayment recovery, allowing the Social Security Administration to recoup funds more aggressively. Because overpayments often result from agency error, the shift exposes retirees on fixed incomes to sudden benefit reductions with little ability to absorb the loss.

Second, the administration eliminated paper checks, requiring beneficiaries to receive payments electronically. While routine for most retirees, the change creates barriers for very elderly Americans and those without stable banking access, turning a technical adjustment into an access problem.

Third, the administration tightened identity verification requirements in the name of fraud prevention. Protecting the system is a legitimate goal, but heightened ID checks often function as gatekeeping devices, particularly for seniors with disabilities, outdated documents, or limited digital literacy.

Taken together, these steps point to a quiet but consequential shift, with the heaviest effects falling on low-income seniors, people with disabilities, and others who rely most heavily on in-person assistance and predictable benefits. Rather than cutting benefits outright, the administration is making Social Security leaner, more automated, and less forgiving. These changes attract little attention, but they shape how millions of Americans experience the program.

The Next Phase: Tax Relief, Reduced Access, and a Shift of Risk

The next round of changes, scheduled for 2026, extends this pattern. Instead of addressing Social Security’s long-term financing challenges directly, the administration has favored measures with short-term political appeal that defer hard choices and shift risk onto beneficiaries.

On the campaign trail, Trump promised to eliminate federal taxes on Social Security benefits. That pledge never became law, largely because doing so would have accelerated the program’s insolvency. Instead, Congress enacted an enhanced tax deduction for Americans aged 65 and older. Beginning in 2026, some retirees will owe less federal tax on their benefits, and some will owe none at all. The relief is temporary, set to expire in 2028, and does little to stabilize the trust fund.

At the same time, the Social Security Administration plans to sharply reduce in-person services. Internal targets call for cutting field office visits roughly in half, accelerating the shift to online and phone-based systems. Field offices have long served as the program’s front door, providing hands-on help with retirement claims, disability applications, and benefit disputes. For seniors with limited digital access or complex cases, digital access is not a convenience but a necessity.

Seen together, these changes reveal a consistent governing approach, one enabled by congressional acquiescence and defined by administrative retrenchment and risk shifting rather than overt benefit cuts. Benefits are not being slashed outright, but access is narrowing, administrative burdens are rising, and fiscal pressures are being postponed. The result is a quieter form of retrenchment that preserves the appearance of stability while shifting real consequences onto millions of seniors, especially those least equipped to absorb new administrative and financial burdens.

Conclusion: A Program That Works, If Congress and the Administration Choose to Protect It

Social Security’s great strength has always been its reliability. It does not promise wealth, but it has delivered something more important: dignity and security in old age. That achievement was not accidental. It reflects deliberate political choices to pool risk broadly, administer benefits simply, and treat retirement security as a collective responsibility.

What is happening now is not the sudden dismantling of Social Security, but something subtler.

Rather than relying on piecemeal administrative changes, Congress and the president should work together on durable reforms that preserve the program’s legacy and strengthen its long-term foundations. An important step Congress could take is to bolster Social Security’s finances through permanent revenue measures, such as raising or eliminating the payroll tax cap so high earners contribute at the same rate as everyone else. Administrative efficiency should not come at the expense of access for millions, so lawmakers should also require a baseline level of in-person service at Social Security field offices. Finally, Congress should assert stronger oversight of Social Security Administration decisions, including reporting requirements and clear guardrails to prevent misguided cost-cutting efforts from undermining benefit delivery.

The danger is not that Social Security will fail overnight, but that it will be slowly hollowed out. A program that still works remarkably well could become harder to navigate, less predictable, and less protective, especially for the seniors who depend on it most. That outcome is not inevitable; it is the result of political decisions. The question now is whether policymakers will honor that legacy by acting decisively to pass sensible, lasting reforms that strengthen the program rather than allowing it to erode.

Robert Cropf is a Professor of Political Science at Saint Louis University.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room